Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves

Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum

|

|

Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum |

Return to Part II

Natural Immunity

|

| Baron Kitasato Shibasaburō |

The study of antibodies first began in 1890 when Japanese physician Kitasato Shibasaburō described antibody activity against the virus while looking at immune blood samples, but the finer mechanics weren't understood until the early 1900s. Unlike most victims, immune hosts will produce antibodies as soon as they start showing symptoms. As explained before, it can take days or weeks for the body to produce antibodies for a new infection. The one exception to this rule is "natural antibodies," which are believed to be the result of microbes native to the body since birth.

Because HVV has such a wide variety of glycoproteins on its surface, it also means more antigen types, which makes the virus much more vulnerable if it happens to have just one antigen that an existing antibody can lock into. The most logical explanation for immunity is that the virus will sometimes share a similar antigen with a microbe the host already developed antibodies for. Whether it's the result of natural antibodies is unknown.

It's quite possible that if it wasn't for this phenomenon, early humans would have been completely wiped out by vampirism.

Since the 1830s, hundreds were institutionalized so they could be used as human blood farms, which was excused as a necessary evil at the time. Even worse, before the discovery of the ABO blood group system in 1900, this ended up killing thousands of recipients due to mismatched donors. This too was brushed off as being a better alternative to vampirism. In addition, the antibodies in each transfusion would only last about three months before a new one was required—otherwise the infection would relapse from an apparent dormancy, since a recipient won't produce their own antibodies as long as they have someone else's. Because of the sheer rarity of compatible blood, this form of treatment was far from reliable, and ended up being a luxury only the very rich could afford. It was a sad irony, humans depending on blood to avoid vampirism.

|

|

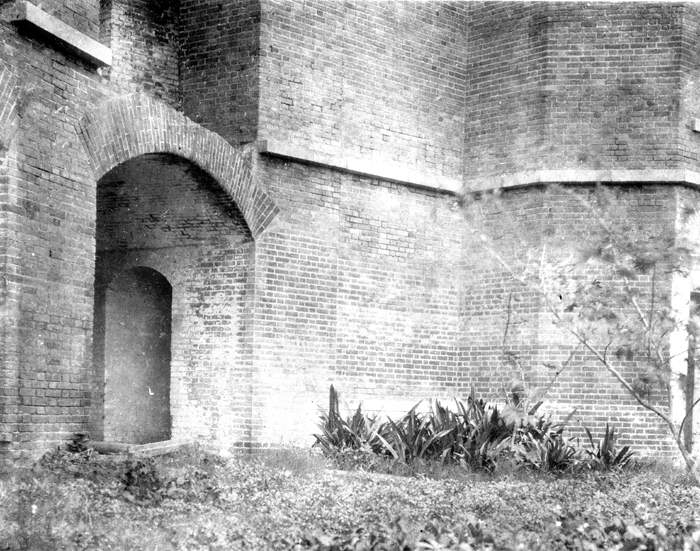

Many vampires were studied behind the walls of this facility in the Dry Tortugas. |

Without a long-term vaccine, infection was basically a death sentence for civilians and agents alike. In the early days of the Agency, these unfortunate individuals would be imprisoned and kept alive for study after they turned. There was, according to historical accounts, a rather hellish facility in the Dry Tortugas for this very purpose, until it was leveled in 1915. In later years, victims were at least given the option of being euthanized, as opposed to facing outright vivisection. It was a difficult scenario for everyone involved, and it certainly didn't help recruitment numbers. Worse, many infected agents would flee and become the organization's most dangerous adversaries: vampires with all the knowledge and training of an FVZA agent.

The 1943 plan that sought to put an end to all this was dubbed the Zozobra Project, after the giant marionette that's built and burned every autumn in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Although this detail has been long forgotten by most, the marionette is actually an effigy of a vampire, as evidenced by its pale face and black eyes. By burning him, people would destroy their worries and troubles in the flames. It was an effective form of catharsis for many who lost loved ones to vampire attacks.

|

| Zozobra (2007) |

The Zozobra Project was an attempt to bring an end to many millennia of vampiric activity by developing a vaccine for the virus. Mindful of what happened to my brother, I signed on.

|

| Zozobra Project housing was rustic at best. |

A day later, in an atmosphere of stone-faced secrecy, I was flown to the Air Force base in Albuquerque and then escorted into the back of a van with no windows. About an hour or so later, I arrived at what could have passed for a summer camp, except for all the scientists milling about.

The scientists of the Project were a true "dream team." Men I had read about in books were now sitting across from me in the lunchroom. As one of the younger scientists, I felt like I was in over my head. But there was no time for anxiety, as reports of vampirism outbreaks were reaching us almost every day.

The early years of the Project were a string of failures. In vaccine work, the objective is to expose the patient to enough of the virus to develop immunity, but not enough to make him sick. With the human vampirism vaccine, it was always the same problem: injections of "killed" virus failed to stimulate antibody production, and injections of the treated live virus caused vampirism. We knew that the secret lay in finding the right way of manipulating the virus before injecting it into the patient.

We did, however, find success in another branch of research: harvesting antibodies from immune blood by separating and purifying the plasma to make it safe for any blood type. This byproduct is known as immune globulin. Once injected into an infected host, these donor antibodies would immediately mark the viral antigens as targets for the immune cells to neutralize. Unfortunately, as with regular transfusions, immunity only lasted about three months before the infection came back. We needed a vaccine for long-term protection, as well as to produce more globulin.

Fortunately, the War ended without the threatened onslaught of vampiric armies; but most of us stayed on with the Project, plugging away. Weeks turned to months, turned to years. To alleviate the stress and isolation, we played chess, watched movies, listened to music, formed a softball team and enjoyed frequent barbecues.

|

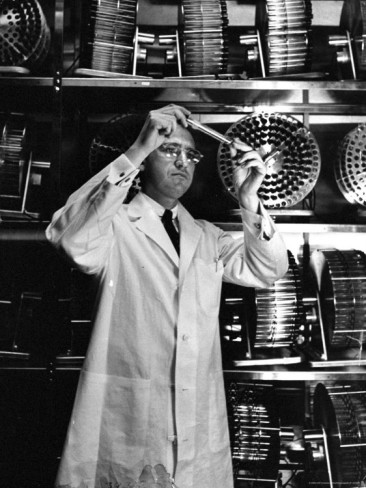

| Harvesting the vaccine |

One would think this would obviate the need for globulin, but vaccine on its own has a major disadvantage: once inoculated, it takes at least a few days for the plasma cells to start producing antibodies. While this is great news for those who can get vaccinated before being bitten, it's completely useless otherwise. The two go hand-in-hand: the vaccine confers years of immunity and produces useful antibodies, while the globulin provides immediate protection until the vaccine can take effect.

Now that we had perfected this duality, we required just one more thing: a human test subject.

By the time we arrived, Valdez had already been cleaned up, treated with antibiotics, and given a blood transfusion to replace the pints he lost to his attacker. After some greetings and introductions, we prepared a small, plastic cooler full of single-dose vials. Using a 50cc syringe, I then administered the globulin: one 10cc shot of viscous, molasses-like serum into the muscle of his left lower neck, right at the bite wound. Opening a cooler of larger vials, we used a 30cc syringe to give him the vaccine: 20 CCs of a more aqueous solution, divided evenly into six patches of abdominal muscle. Despite his bite-induced drowsiness, the whole regimen was far from pleasant for him.

It was a long day and night as Mr. Valdez tossed and turned with fever, before slipping into a vampiric coma. We saw this coming thanks to our animal testing, but it barely put a dent in our anxiety. Following cautionary procedures, we restrained the unconscious man and made preparations to euthanize him if he started to show definite signs of transformation—with his signed permission, of course.

When morning finally came, we checked on Mr. Valdez in his room. Much to our amazement, we found him awake with no further symptoms!

|

|

A certain doctor examines Joe Valdez six weeks after he received the vampirism vaccine. |

During this time, we got back to work harvesting more vaccine from our chicken eggs, while hundreds more patients arrived for treatment. We could only accommodate five more people for follow-up shots, observation and blood donation, but we sent the others to local and state hospitals for that purpose. Many gallons of inoculated blood was harvested, which we were able to synthesize into more globulin. Soon, entire stockpiles were shipped out all over the country and the rest of the world, forever stunting the spread of this terrible affliction. Even better, none of our patients showed any signs of relapse!

|

|

Working at the Santa Rosa Institute; 1955 |

After we wished him and his fellow patients a heartfelt goodbye, Joe Valdez returned to his home in Santa Fe, where few would know of his historic contribution to society. He lived a long, quiet life with his family, and died of natural causes in 1994.

To this day, no viral relapse has ever been reported to occur in recipients of the HVV vaccine.

Vaccine and globulin production peaked in the late 1950s and tapered off after that. No new batches were produced after 1965. The CDC estimates it has a combined total of 250,000 doses on hand—far too little to treat a full-scale outbreak. They claim that existing vials can be diluted to stretch out the supply, but there are no studies to support this. Not to sound too alarmist, but if an outbreak occurred today, it would take several months to ramp up vaccine production, during which time the outbreak could have claimed millions.