Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves

Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum

|

|

Historical Tales | News | Vampires | Zombies | Werewolves Virtual Academy | Weapons | Links | Forum |

Return to Part V

Body Temperature & Dormancy

|

|

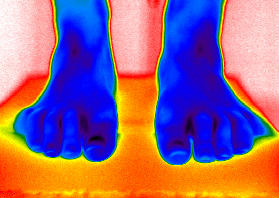

Seen through thermal vision, a vampire attacks its prey. |

This temperature anomaly proved to be a great help for modern vampire hunters, as it made vampires easily distinguishable from humans when viewed through infrared imagery.

For important chemical reactions, vampires have at least two "emergency" enzyme systems that each operate at either freezing or feverish temperatures. While not nearly as efficient as their more moderate counterpart, they at least allow the body to survive a wider range of core temperatures than humans and other mammals, if typical regulation is not an option. This is known as poikilothermia, another characteristic vampires share with the naked mole-rat.

Because their body temperature is dependent on environment and they are unable to bask in the sun like reptiles can, sick vampires cannot experience or (sans hot weather) induce consistent fevers to slow the growth of harmful infections, but the natural antibiotics in their bodies more than fulfill this purpose.

|

| A vampire's cold feet on a heating pad |

Despite their aversion to the cold, vampires will not freeze to death—even when frozen solid. Like the wood frog, their bodies can quickly produce and accumulate higher levels of urea and glucose, which act as cryoprotectants by limiting the formation of internal ice crystals while reducing osmotic shrinkage of cells. However, while wood frogs can survive this way for only seven months at most, vampires have been known to last as long as 40 years—a decade longer than frozen tardigrades. As with the latter organism, this ability to remain desiccated for extended periods is largely dependent on high levels of the nonreducing sugar trehalose, which protects their cell membranes even after the event of osmotic dehydration.

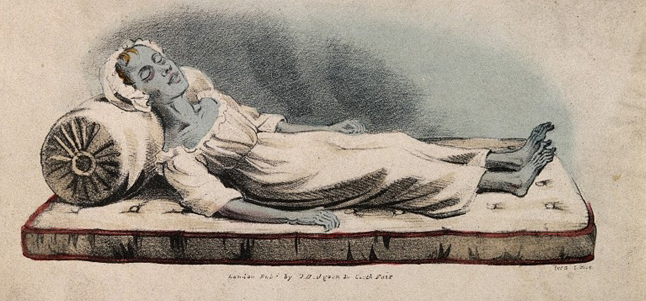

If food is scarce, or if the situation is less than hospitable, even temperate vampires can go dormant and hibernate voluntarily, provided they're well-fed and can find a safe place to construct a lair. Abandoned buildings, mines and caves are high on the list of potential lair sites. Once safely ensconced, the vampire will fall into a deep sleep, during which its bodily functions slow to a level just enough to sustain it. Respiration drops to only one breath every six to eight hours (depending on temperature), circulation slows to only three to six fasciculations per hour, and hair and nail growth grinds to a halt. The longer a vampire hibernates, the more dried and withered it becomes as its body uses up nutrients; rate of hair loss is about the same as an active vampire. In time, it may resemble a mummified corpse or wax sculpture, which can be dangerously deceiving to whomever may discover it.

|

|

19th-century depiction of a vampire during a normal sleep cycle. Dormant vampires tend to lay flat on their backs or curl into a fetal position, usually with their arms crossed. In addition, they will typically strip naked as extra body heat can be detrimental to a long dormancy. |

As long as they take these so-called lunch breaks, and feed on a live human every ten years, there appears to be no limit to how long they can hibernate. The longest record was discovered in 1964 when a construction crew in London uncovered a vampire that had been dormant since 1688—almost 280 years! Interestingly, it was found inside the remains of an old wine cellar in the Whitechapel area, near the site of one of Jack the Ripper's murders.

This ability to go long intervals without blood begs the question: why do so many vampires die of starvation? The simple answer is that they simply become addicted to the taste and effects of blood, so they remain active to feed as much as possible. It actually takes a fair amount of self-discipline to simply lay down and give that up. Another important reason is that vampires have to gorge themselves on human blood in order to get them through at least three years of inactivity, which is impossible if they're already starving and unable to hunt. Non-human mammals do suffice, but this only gives them a year at most, and a human meal is absolutely required afterward.

As for why dormant vampires don't suffer from pressure sores and muscle atrophy: like bears, vampires will periodically stretch, shiver and reposition their bodies to simultaneously exercise their muscles and improve circulation. This occurs about three to four times a day in bears, but only once or twice a week for a vampire. Muscle wasting in both species is also suppressed by a proteolytic inhibitor which is released into the bloodstream.

|

|

What little sperm that can be harvested from vampiric testes is always highly deformed. |

|

|

A nude vampire corpse on a makeshift autopsy table. Right-click for full size. |

Alterations to the brain's structure and chemistry are responsible for a vampire's lack of gender identity and apparent asexuality, which would explain why they aren't picky as to which gender to feed on. That's not to say that vampires don't feel affection for the people they knew; but tragically, most of them can't stop themselves from making loved ones their first victims.

As one might suspect, there have been many reports throughout history of troubled individuals who purposely got themselves infected in order to rid themselves of their sexuality, such as frustrated virgins and sex addicts, shunned and self-loathing LGBT individuals, victims of rape and adultery, those who had committed adultery, priests who had broken their vow of celibacy, and rapists who felt remorse for their crimes.

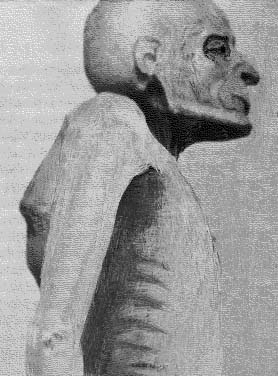

Because they presented such a danger to society, most vampires were destroyed long before the outer limits of their lifespan were determined. Ancient history offers some clues, however. In ancient China, there was said to be one vampire in the Emperor's court through the entire Eastern Zhou Dynasty, which would put his age at 550. More accurate modern records have certified vampires of over 300 years old.

|

|

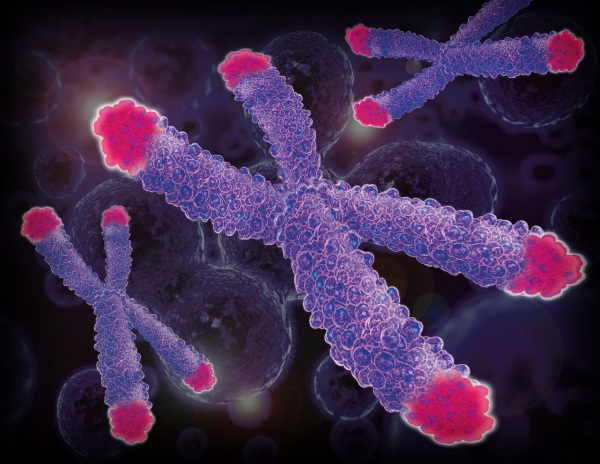

Chromosomes (purple). Telomeres (pink). |

Like naked mole-rats, vampires also have a high resistance to tumors—at least those of the malignant variety. In addition to the slowed aging process, the proliferation of cancerous cells is further inhibited by an "over-crowding" gene which prevents cellular division once individual cells come into contact—a mechanism known as "contact inhibition." Basically, vampiric cells will commit mass suicide when overcrowded, thus preventing tumor formation.

|

|

A 125-year-old vampire photographed in Spain; 1901. Note the curved spine, lack of hair and emaciated frame. |

|

|

Vampires cease growing when they're turned before adulthood. |

|

|

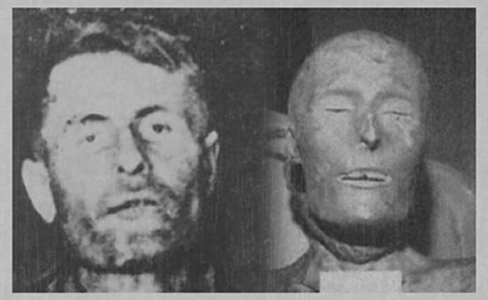

Elmer McCurdy, an Oklahoma outlaw who was turned in 1911 at age 31. The second photo was taken after his sunburnt body was found hanging from a tree in 1959. He had also filed his fangs down, inserted needles into his flesh, and castrated himself. |

|

| A rabid canine |

Unlike vampires, non-humanoid coma survivors do not experience dental growth, and are completely rabid from brain swelling. Cancer, tissue necrosis and immune disorders occur as well, and also shed light on how early proto-vampires may have started out. One reason for these problems is that not as many cells can be infected and transformed, causing tissues to become mismatched and identified as foreign by the rest of the body. In addition, some degree of viral production will continue even after the coma, which only causes further cell destruction. This biological incompatibility with the virus is always fatal: the vast majority of primates live less than a week; non-primates even sooner.

The virus' effect on animals raises an important question: why us? Why is the virus so much more compatible with our bodies? After all, the rabies virus doesn't treat us any better than other mammals. While it's perfectly plausible that millions of years of natural selection could craft the vampires we know today, it would require relatively constant exposure, death and re-exposure to weed out the problems seen in other animals. As disturbing as it is to consider, vampires could have very well been bred like dogs.